“Ghost Guns” Facts!

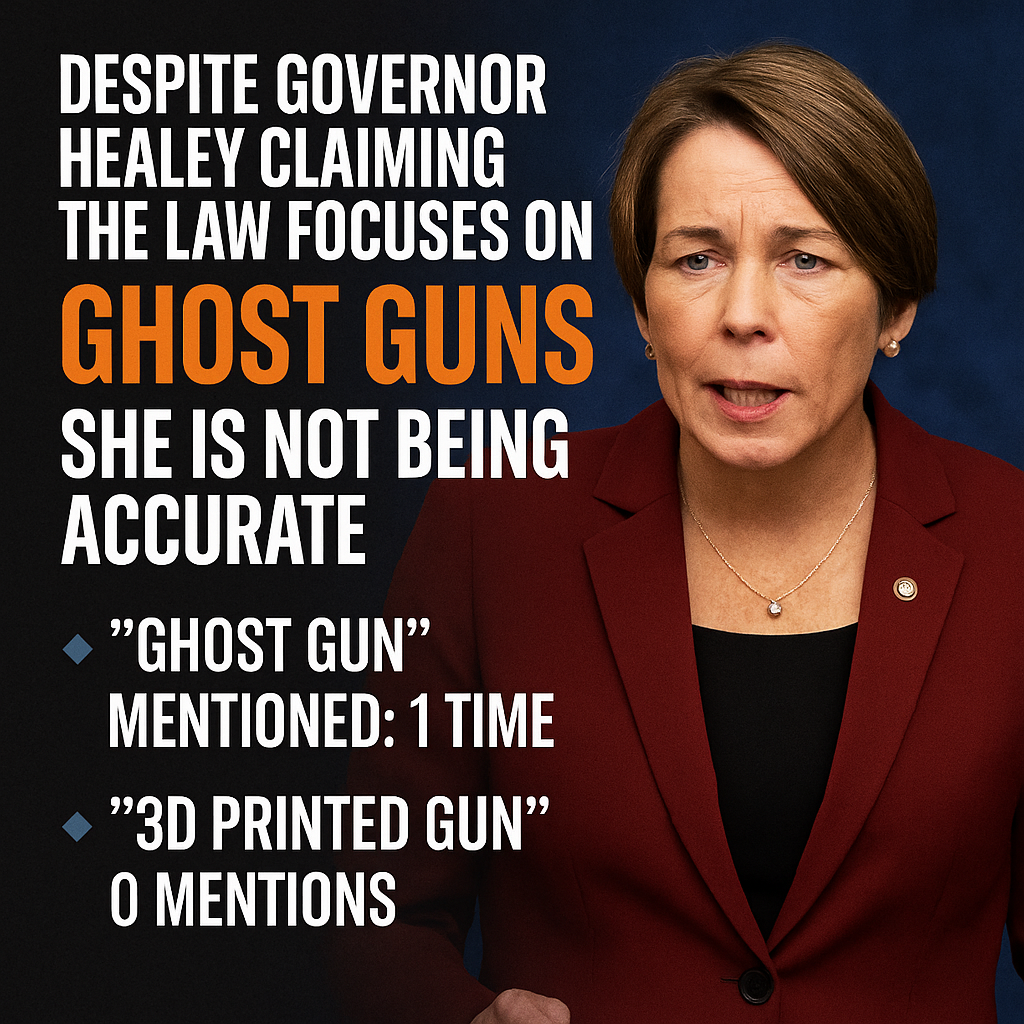

“Despite being promoted as a ‘ghost gun crackdown,’ Chapter 135 mentions the term ‘ghost gun’ exactly once in over 116 pages of legal mandates. The phrase ‘3D printed gun’ appears zero times.

What it does contain are sweeping restrictions and registration requirements that impact every law-abiding gun owner in Massachusetts—without addressing the core sources of violence. The law’s scope reveals the truth: this isn’t a targeted fix for ghost guns, it’s a broad constitutional overreach under the guise of safety.”

The term “ghost gun” has become a centerpiece in contemporary debates about firearm regulation, describing untraceable firearms that lack serial numbers. While the term evokes images of lawlessness and unaccountability, the concept of untraceable guns is neither new nor inherently malicious. Historically and in modern times, firearms have been privately made without serial numbers for personal use, often in the absence of regulatory frameworks. Understanding the origins of the term and the motivations of modern firearm hobbyists’ sheds light on the nuanced reality behind the “ghost gun” debate.

Origins of the Term “Ghost Gun”

The term “ghost gun” was first coined in 2012 and propagated by gun control advocacy groups such as Everytown for Gun Safety and the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, both of which have played a significant role in bringing attention to the perceived dangers of untraceable firearms. These organizations are not grassroots movements; they are well-funded entities supported by prominent donors and influential interest groups with specific political leanings. Research into marketing studies revealed that the term resonated strongly with voters, as it invoked fear and urgency about firearms that could allegedly evade law enforcement scrutiny.

Everytown for Gun Safety, for instance, is heavily backed by billionaire Michael Bloomberg, former mayor of New York City and a vocal advocate for stricter gun control measures. Bloomberg has dedicated substantial financial resources to advancing Everytown’s mission, which aligns with progressive and Democratic Party policy platforms advocating for tighter firearm regulations, universal background checks, and restrictions on firearms deemed to pose heightened risks. Similarly, the Giffords Law Center, co-founded by former Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords following her near-fatal shooting in 2011, receives funding from various “progressive” philanthropic foundations and individual donors that generally lean toward extreme liberal political ideologies.

These organizations operate as part of a broader coalition of liberal & socialist advocacy groups, think tanks, and political action committees that seek to influence public policy and legislative priorities surrounding gun control. Their campaigns often target elected officials, leveraging significant financial resources to promote specific legislative agendas, such as banning certain firearm components or increasing federal oversight of privately made firearms.

The financial and political backing of these organizations reflects their broader mission to shape public opinion and influence gun control legislation. By coining emotionally charged terms like “ghost guns,” they aim to create a narrative that highlights the risks associated with untraceable firearms while rallying support for stricter regulations. However, their financial and ideological backing also underscores their alignment with a particular set of political values, which may not resonate universally across the spectrum of public opinion.

Understanding who supports these organizations and their political leanings provides valuable context for interpreting their messaging and objectives. While their efforts have undeniably raised awareness about firearm-related issues, critics argue that the financial and political influence behind these groups can lead to one-sided narratives that oversimplify complex issues and fail to account for the perspectives of lawful gun owners and hobbyists. This dynamic highlights the importance of engaging with diverse viewpoints and fostering a balanced, evidence-based approach to firearm regulation that considers both public safety and individual rights.

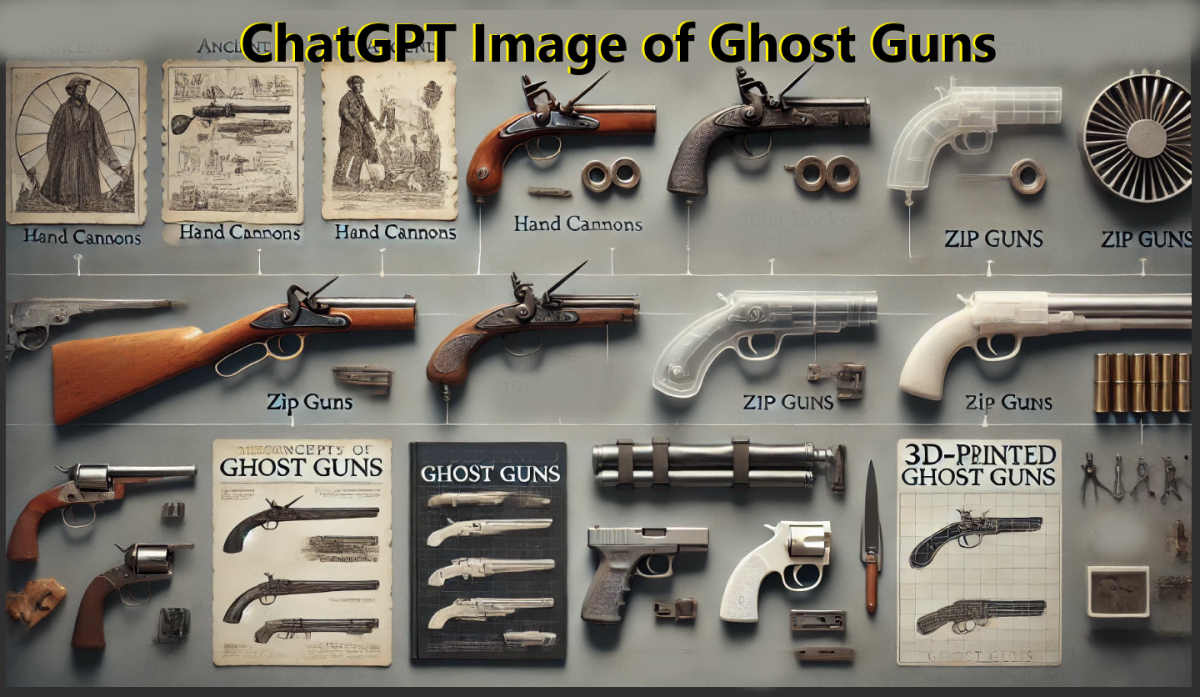

A Historical Perspective: Firearms Before Serial Numbers

Before the Industrial Revolution, all firearms were, in today’s terms, “ghost guns.” Firearms were crafted by skilled gunsmiths, typically operating as independent artisans or small workshops, without the large-scale industrial infrastructure that would later revolutionize manufacturing. These weapons were intended for personal use, local trade, or specific commissions and were individually handcrafted to meet the unique needs or preferences of their users. Instead of standardized identifiers, gunsmiths often marked their creations with decorative emblems, personalized engravings, or their names, serving more as a signature of craftsmanship than a method of tracking ownership or origin.

The lack of serial numbers on these early firearms reflected the technological and societal norms of the time. Without a centralized system of regulation or widespread mechanisms for law enforcement to trace weapons, there was little need for unique identifiers. Additionally, in a pre-industrial economy, firearms were produced in relatively small quantities, often tailored to a single buyer or community, further reducing the necessity for serialization. Each weapon was unique, distinguishable by its design and maker’s mark rather than a mass-production identifier.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, this dynamic began to change. Industrialization brought mass production techniques, enabling firearms to be manufactured on a much larger scale. This shift necessitated the introduction of serial numbers for practical reasons, such as inventory control and quality assurance. Factories needed a systematic way to track their production, manage stock, and address potential defects in their products. Serialization allowed manufacturers to identify individual firearms within large batches, facilitating repairs, recalls, and quality control processes.

Despite these practical applications, serial numbers were not initially tied to government regulation or law enforcement. It wasn’t until the mid-20th century, with the Gun Control Act of 1968, that the U.S. government mandated serial numbers on all commercially sold firearms. This legislation aimed to aid law enforcement in tracing firearms used in criminal activity, providing a crucial tool for investigations. By associating a firearm with its original point of sale and initial purchaser, serial numbers became a key component of efforts to combat illegal gun trafficking and reduce gun-related crimes.

Prior to this regulatory shift, the absence of serial numbers on firearms was not an intentional effort to avoid accountability or regulation. It was simply a reflection of the societal, technological, and legal context of the era. The concept of centralized firearm control was largely foreign to pre-industrial societies, where governance was more localized, and individuals were often responsible for their own security. In this context, the personal and artisanal nature of firearm production made the idea of unique serial identifiers unnecessary and irrelevant.

The evolution from handcrafted, personalized firearms to mass-produced weapons marked by serial numbers illustrates a broader transformation in the relationship between technology, society, and regulation. It underscores how changes in manufacturing processes and societal priorities can drive the development of new systems of oversight and accountability, shaping the ways in which firearms are produced, sold, and monitored.

Modern Hobbyists: A Continuation of Tradition

Today, many firearm enthusiasts continue the long-standing tradition of crafting firearms for personal use, a practice that remains legal under U.S. federal law so long as the firearms are not sold or transferred. These hobbyists often assemble firearms from kits, custom parts, or even raw materials, engaging in an activity that reflects both personal creativity and technical skill. For many, this is not just a functional pursuit but also an expression of personal freedom, a testament to engineering ingenuity, and a way to connect with the historical craftsmanship of firearms.

A common misconception is that firearms can simply be 3D-printed and immediately used. This notion, often perpetuated in sensationalized narratives, fails to acknowledge the reality of firearm construction. While 3D printers can produce certain components, such as lower receivers or non-load-bearing parts, the creation of a functional, reliable firearm requires much more than a push of a button on a printer. Critical components, such as barrels, bolts, and other load-bearing parts, must be made from strong, durable metals capable of withstanding the intense pressure and heat generated when a firearm is discharged. These parts cannot be effectively or safely made using standard 3D printing materials like plastics or resins.

Attempting to fire a fully 3D-printed firearm would likely result in catastrophic failure, with the firearm exploding or breaking apart due to the inability of printed materials to handle the forces involved. To create a functional and safe firearm, enthusiasts must possess not only machining skills and access to specialized equipment but also a deep understanding of material science and firearm mechanics. Machining metal components to the precise tolerances required for a working firearm is a time-intensive and highly technical process, far beyond the capabilities of casual or unskilled users.

This reality underscores the motivations of lawful hobbyists who engage in firearm crafting. For these individuals, the process is as much about the journey as the destination. It often involves significant time, effort, and investment in tools and materials. The craftsmanship required to create a functioning firearm fosters a sense of accomplishment and pride, similar to other forms of skilled workmanship, such as woodworking or model engineering. Additionally, many hobbyists view their work as a way to preserve and celebrate historical traditions, often replicating designs or techniques from earlier eras.

By engaging in this tradition, hobbyists are exercising a combination of rights, creativity, and technical expertise. They contribute to a niche culture that values self-reliance, innovation, and a connection to history. Their motivations stand in stark contrast to criminal misuse and underscore the importance of distinguishing lawful firearm crafting from illicit activities. Recognizing the effort and skill involved in this practice helps to demystify the process and adds an important layer of understanding to discussions about firearm regulation and the rights of hobbyists.

Challenges of Serializing Homemade Firearms

One of the most significant challenges for hobbyists is compliance with modern serial-numbering requirements. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) mandates that serial numbers be engraved to specific standards—at least 0.003 inches deep and no smaller than 1/16 of an inch in height. Achieving this requires industrial-grade equipment that most hobbyists do not have, making serialization impractical for many.

Intentions of Hobbyists

Despite public narratives implying otherwise, there is little evidence to suggest that most hobbyists manufacture firearms to evade law enforcement. Instead, they view firearm-making as a form of craftsmanship and personal empowerment. The legality of manufacturing firearms for personal use further supports the notion that hobbyists are not acting with malicious intent but rather exercising their rights under the law.

The “Ghost Gun” Debate: Assumptions vs. Reality

The rise of the term “ghost gun” has been accompanied by assumptions about the motivations and actions of DIY (Do It Yourself) gunmakers. Critics argue that the untraceable nature of these firearms makes them attractive to criminals. However, available data does not support the notion that self-manufactured firearms are a primary driver of crime. Studies have shown that most firearms used in criminal activity are professionally manufactured and acquired through illegal means, such as theft or straw purchases.

Historical Parallels

If today’s standards were applied retroactively, all pre-industrial firearms would be classified as “ghost guns.” The lack of serialization on historical firearms was a product of the time, not an effort to avoid accountability. Similarly, modern DIY firearm makers can be seen as part of this historical tradition rather than actors with nefarious intent.

A Marketing Strategy by Extremists on the Left

The term “ghost gun” itself is a calculated product of strategic framing by various advocacy groups aiming to influence the conversation around firearm regulation. By using a term that evokes imagery of secrecy, danger, and unaccountability, these groups have successfully tapped into public fears and concerns about crime, law enforcement challenges, and public safety. This emotionally charged language not only captures attention but also creates a sense of urgency, steering the narrative in a way that amplifies the perceived threat posed by untraceable firearms.

The success of this framing lies in its ability to simplify a complex issue into a term that is easy to understand and compelling for media coverage, public discourse, and political debate. However, this simplification often comes at the cost of nuance. It lumps together a diverse range of practices and intentions under a single, highly charged label, failing to differentiate between lawful, historically rooted hobbyist practices and the illicit manufacture or use of firearms for criminal purposes. As a result, lawful firearm enthusiasts who engage in crafting or assembling firearms for personal use may find themselves unfairly stigmatized or mischaracterized as contributing to broader societal risks.

Moreover, the framing of “ghost guns” as inherently dangerous or illicit has significant implications for policy development. Policymakers and legislators, influenced by public fear and media narratives, may prioritize restrictive measures that fail to address the root causes of firearm misuse while placing undue burdens on lawful hobbyists. This one-size-fits-all approach risks alienating responsible gun owners and enthusiasts, whose motivations are often tied to personal freedom, historical appreciation, and craftsmanship rather than criminal intent.

The term also reinforces a binary perspective that oversimplifies the reality of untraceable firearms. It neglects the historical context in which privately made firearms have existed for centuries and overlooks the legitimate, often legal, activities of individuals who make or assemble firearms for personal use. By framing all untraceable firearms as “ghost guns,” the discourse often fails to account for the significant differences in motivations, practices, and outcomes associated with these weapons.

In shaping both public opinion and legislative priorities, the term “ghost gun” highlights the power of language in influencing societal perspectives. However, it also underscores the need for greater precision and balance in how these issues are discussed. An emotionally resonant term like “ghost gun” may galvanize support for regulation, but it can also obscure the legitimate and legal dimensions of firearm ownership and crafting, potentially undermining a nuanced and effective approach to public safety. To advance meaningful solutions, it is essential to move beyond emotionally charged language and toward a data-driven, contextually informed understanding of the issues surrounding untraceable firearms.

A Call for Balance and Truth

The debate about ghost guns is suffering from blurry lines between lawful hobbyists and criminal actors; conflating the two risks alienating those people making firearms as a legitimate hobby and overlooks rich history for self-reliance and craftsmanship best pre-dating modern regulation.

Data-driven solutions by policymakers and advocates that address criminal misuse and yet do not infringe upon the rights of hobbyists would be key. The history of legitimate motivations by DIY gunmakers in making untraceable firearms provides a well-placed view. An acknowledgment of such should therefore yield a balancing act on firearm regulations.

While the term “ghost gun” has been effective to frame the discussion, the reality underlying those firearms tells a story deeply steeped in tradition, ingenuity, and a form of expression of personal liberty.

We can develop policies that honor public safety and individual rights by fostering truth & facts over fear.